By Sean Shields, Structural Building Components Association

As this article series has pointed out several times, metal plate connected wood trusses are incredibly efficient framing elements that can distribute loads over long spans. In simple terms, a truss accomplishes this feat by using alternating

structural framing elements that are either in compression or tension. Fortunately, you don’t have to be a professional engineer to appreciate that this interplay within a truss makes every element of a trusses design, from the grade of the lumber to the arrangement of each interior web, incredibly vital to its ability to perform as intended.

Because every element is important, this article is going to focus on truss damage and best practices installers can follow to ensure damage to a truss element doesn’t become a significant issue in relation to the structural integrity of a building over time.

It’s Not Like a Chain

First, it’s important to note that trusses are not like a steel chain. Chain links are uniform in the way they distribute tension loading and so the adage is true that a chain is only as strong as its weakest link. Conversely, trusses do not distribute load uniformly throughout each truss, or even from truss to truss in a system. Because of this complex interplay, it is exceedingly difficult to just look at damage to a truss in the field and know how that damage may impact the long-term performance of the truss system.

It’s Not About the Worst Case

Obviously, significant damage to one or more critical aspects of the trusses in a system can potentially lead to a partial or complete failure of the whole system. This is the worst case, and, to be clear, it is not the focus of this article. Rather, let’s look at the consequences of less obvious damage and the best practices for avoiding those outcomes.

It’s About Avoiding Guesswork

Several of the previous articles in this series focused on the best practices of storing, handling, and lifting trusses to avoid lateral bending and other activities that most commonly lead to truss damage. Many times, damage caused by these activities comes in the form of checks, splits and cracks in the wood members and/or metal connector plates that either bend or pull out from the wood at the joints.

The challenge is that while damage like this can typically be repaired in the field, sometimes the repair is more difficult or costly than delivering and installing a replacement truss. Even a veteran installer should not make a visual conclusion on how a truss can be repaired in order to perform as intended. This should be left to a design professional with access to all the information associated with the truss design, which is typically found within the design software.

This is why component manufacturers (CMs) are quick to point out in their construction documentation that trusses should not be altered in any way (which includes damage) without the assistance of a building designer, truss designer, or the manufacturer. Any alteration, including damage, can impact performance and only the CM will be able to correctly ascertain how to remedy it.

It’s About Avoiding Headaches

If truss damage is not caught and addressed before or during initial installation, the remedy can go from a minor

inconvenience to a major headache quickly. Again, sometimes a truss repair isn’t possible or efficient and a new, replacement truss is the best option. If the trusses are installed and sheathing is applied, it becomes a lot more difficult and time consuming to rip out and replace a truss.

Similarly, if mechanical, electrical and plumbing (MEP) infrastructure is installed before a truss repair is completed, it may be difficult or impossible to pursue the best repair method because the MEP is in the way. In this case, the consequence is typically a more expensive and time-consuming repair.

As another example, late detection of damage to a truss that ties into a multi-ply girder may mean that a different hanger will need to be used, forcing installers to remove the hangers already attached to the girder. The removal of that hanger may prompt the need to apply a repair to the girder as well.

A more subtle form of truss damage comes in the form of connector plate damage or plate pull out, typically caused on the jobsite due to excessive lateral bending. (See “The Plane Truth” in the November 2020 issue for best practices to avoid this kind of damage.) This kind of damage may lead to long term performance issues where the trusses deflect (bend out of plane) more than designed, which can lead to issues like drywall cracking. Plate pull out in agricultural buildings also exposes more of the metal to moisture and corrosive conditions that can shorten the life of a truss.

It’s About Small, Simple Steps

Fortunately, the best practices for avoiding any and all of these consequences is not difficult to implement. First, truss bundles should be visually inspected either at the time of delivery, or as soon as possible afterward. If there is any noticeable damage that occurred during delivery, the CM should be contacted immediately and, if possible, a digital photo of the damage should be sent to the CM so they can begin designing the repair or scheduling the production and delivery of a replacement truss. The sooner the CM is contacted, the less disruptive the remedy will be to the installation process.

Sending a digital picture of the damage may also enable the CM to deem only a simple repair is needed and the truss can be stabilized with a temporary scab during the lifting and installation process. This avoids any potential delay in the construction schedule while a repair is designed and the temporary scab can either be removed or incorporated into the repair after installation (but before sheathing or MEP is applied).

It’s About Industry Best Practices

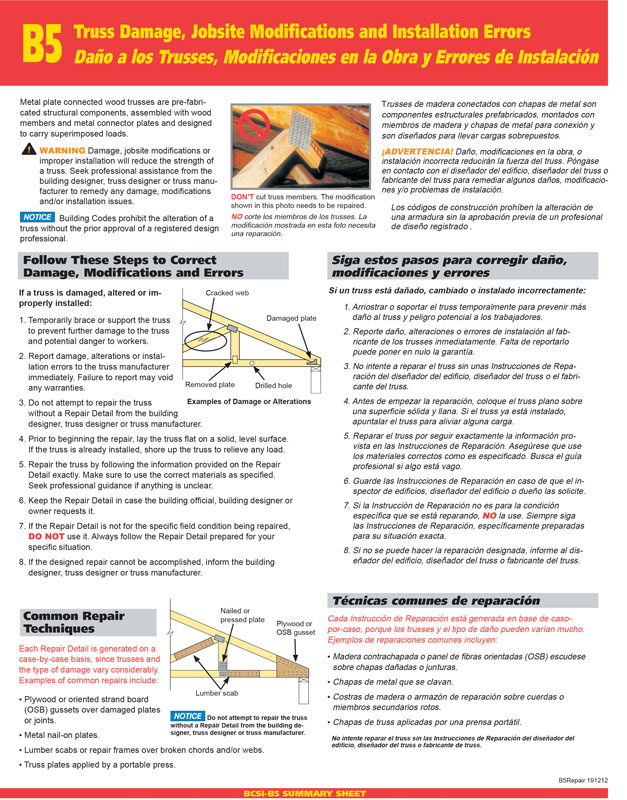

Along these lines, the Building Component Safety Information (BCSI) Handbook-B5 Summary Sheet, “Truss Damage, Jobsite Modifications & Installation Errors,” provides the following steps to correct truss damage on the jobsite:

1. Temporarily brace or support the Truss to prevent further damage to the Truss and danger to workers.

2. Report damage, alterations or installation errors to the Truss Manufacturer immediately.

3. Do not attempt to repair the Truss without a Repair Detail from the Building Designer, Truss Designer or Truss Manufacturer.

4. Prior to beginning the repair, lay the Truss flat on a solid, level surface. If the Truss is already installed, shore up the Truss to relieve any Load.

5. Repair the Truss by following the information provided in the Repair Detail exactly. Make sure to use the correct materials as specified. Seek professional guidance if anything is unclear.

6. Keep the Repair Detail in case the Building Official, Building Designer or Owner requests it.

7. If the Repair Detail is not for the specific field condition you are repairing, do not use it. Always follow the repair Detail prepared for your specific situation.

8. If the designed repair cannot be accomplished, call the Building Designer, Truss Designer or Truss Manufacturer.

Throughout the installation process, it’s also a good practice to quickly review each truss as it’s picked and after it’s installed, particularly if any lateral bending occurs during the installation process.

Bottom Line

It’s important for installers to review trusses at the time of delivery for damage and follow best practices for minimizing the risk of truss damage during material handling and installation on the jobsite. If a truss is damaged, installers should

immediately contact the CM and send them a digital photo of the damage. This will allow the CM to work quickly to issue either an approved truss repair or produce and deliver a replacement truss. Taking this overall approach will minimize impacts to the construction schedule and eliminate potential headaches later when the building is more fully enclosed. FBN

Sean Shields is Director of Communications for the Structural Building Components Association (SBCA, https://www.sbcacomponents.com) and has authored over a hundred articles focused on structural framing and off-site construction since 2004.