By Linda Schmid

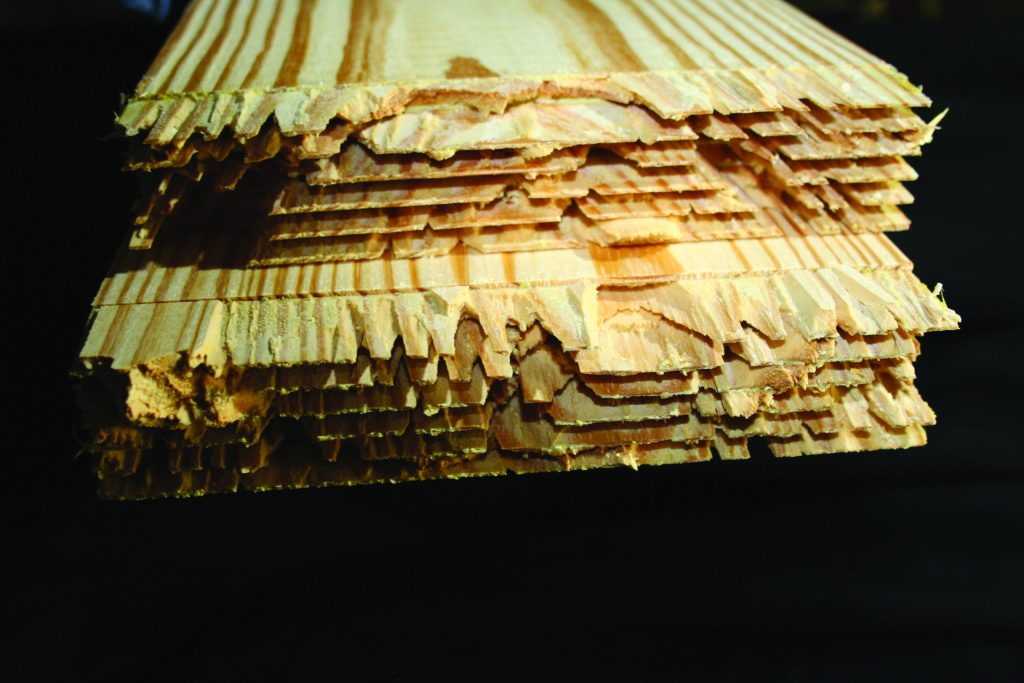

Before jumping into testing, let’s take a moment to talk about laminates in post frame building. The basic idea is, of course, to take smaller pieces of wood and combine them into larger pieces, thereby creating columns for the frame. Besides creating a larger building component, there is the question of how strong the resultant material is. Did it gain or lose strength through the process, and more importantly is it strong enough for your project?

Dale Schiferl, co-owner of Timber Technologies Inc., states that it depends on a number of components like the type of wood used, how the laminate is jointed, and testing to verify the process.

Wood Used

Typically southern yellow pine, spruce and Douglas fir are used, and since they can be similar in strength, Schiferl said they base it mainly on availability and affordability. Machine stress rated lumber (MSR) has been evaluated by mechanical stress rating equipment, so you have a pretty good indicator of how it will perform.

“Some species are easier to glue than other species, and may require less surface prep and pressure to laminate,” Schiferl said. For example, Douglas fir and MSR spruce are easy to face bond. Yellow pine is more difficult due to its cellular structure; it’s overall a denser piece of wood so it requires a more stringent manufacturing process.

To make it even more predictable, you can get yellow pine or most lumber with a machine stress rating.

Laminate Tests

One of the most important tests is the finger joint test, according to Schiferl. The finger joint is where two wood pieces come together to create one longer piece. It has “fingers” cut into the wood ends which fit together and are held with glue. The test puts tension on the joint by applying a load, and increasing until the joint gives.

Another critical test is the cyclical delamination test. The point of the test is to put the glue laminate wood through a 30-year life cycle in the space of 15 hours. This is done by weighing the glue laminate wood, placing it in a sealed vessel filled with water, pulling a vacuum, thereby saturating all of the wood cells. Then the laminate is placed in an oven and dried to its original weight. These extremes are akin to a 30 year life cycle. After the original weight is acheived, the “forensics” begin. The question is: did the glue line hold up throughout the process?

A third test is a shear test. The laminate is set on edge, a piece is sheared off, and the cut edges are analyzed. Are fibers torn? If there is no ragged wood fiber, then the the lamina did not properly adhere. If that is the case, the wood may be too wet or too cold during the lamination process, or it may not have had proper surface preparation or pressure.

Manufacturer Testing

Laminate testing is voluntary, at least testing by a third party is voluntary. Schiferl says that Timber Technologies does third party testing, which means that their product is tested every day. They pull their products randomly from the manufacturing line, test these samples, and record the values. The third party inspector comes in periodically to examine their results and they can view the values over time through the paper trail they are creating day by day. Third party testing allows their products to be code compliant nationwide.

Laminate Considerations

• All things being equal, finger joints are stronger than butt joints.

• Check whether your supplier is third party tested. If they are not, you cannot determine if their laminate wood will fulfill your requirements. FBN