In today’s building construction market, builders and customers are using timber more and more for its sustainability, environmental friendliness, and minimal carbon footprint. It’s lighter in weight than steel or concrete, and erection is faster. There are many different types of timber and engineered wood products currently available for frame building construction that perform well as structural elements.

Durable and attractive, they offer a range of benefits over other building materials. Two of the most common are glued laminated timber (also called glulam) and nail laminated timber or nail lam or NLT. What follows is a comparison between the two.

Glulam

Glulam is a type of structural engineered wood product comprising a number of layers of dimensional lumber bonded together with durable, moisture-resistant structural adhesives. Glulam is made of a longer and larger piece of building material composed of smaller pieces of lumber. This allows glulam to be made from younger trees from second and third growth forests, and this makes glulam relatively sustainable and faster to replenish than larger pieces of whole timber from older, bigger trees. Glulam is stiff and sturdy, and can be bent and shaped.

Glulam is one of the oldest forms of timber used in construction; it dates back to 1866. It was patented in 1872 in Germany. In 1942, fully water-resistant

phenol-resorcinol adhesives were introduced that made it safe for outdoor use. The wood is all oriented in one direction, so it acts like a solid piece of wood.

Because the layers of wood are all oriented in the same direction, it can shrink or expand in length, just like solid wood. Per the APA — The Engineered Wood Association — standard glulam members range from 6 inches to 72 inches in depth and 2.5 inches to 10.75 inches in width. Components are cut to length when ordered and can surpass 100 feet.

To form a glulam component, dimensional lumber is positioned according to its stress-rated performance characteristics. In most cases, the strongest laminations sandwich the beam to absorb stress proportionally and ensure longevity. Multiple plys and lengths are engineered or designed for specifications with higher design values than solid or nailed columns.

Dale Schiferl, principal at Timber Technologies, Colfax, Wisconsin, uses different types of glulam adhesives. “One particular type for structural finger joints and one type for face gluing,” he said. “Both are common two-part adhesives used for engineered wood products such as glue lam, lvls and ‘I’ joists.”

Mike Momb “The Pole Barn Guru” who is the technical director at Hansen Pole Buildings, Browns Valley, Minnesota, cautioned that glulams should only be factory assembled, in controlled temperature environments.

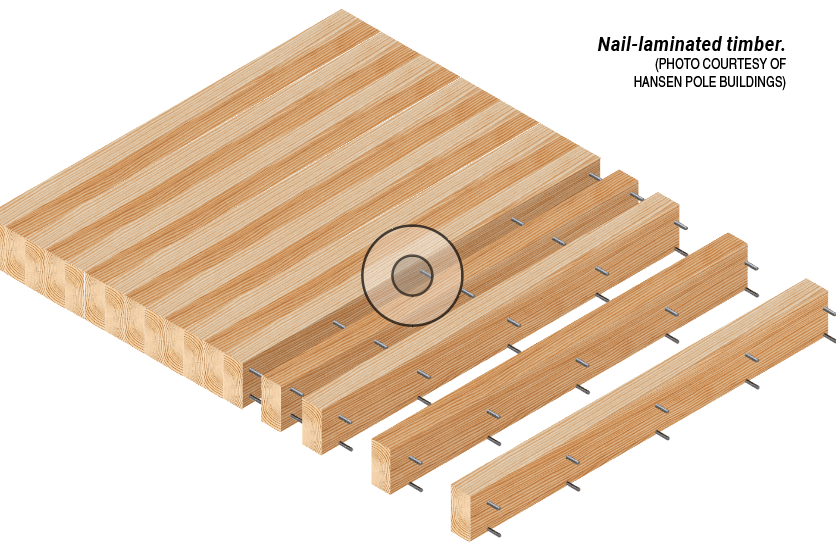

Nail Laminated Timber

NLT is an affordable and easy to produce a form of laminated timber. It’s been around a long time and used to be called mill decking or heavy timber. To create NLT, dimension lumber is placed on edge with individual laminations mechanically fastened together with nails or screws. Its strength and durability comes from these nails and sometimes screws that fasten the individual pieces of dimensional lumber into a single structural element. The geometry of the NLT construction is similar to glulam because you are laminating dimension lumber on top of one another. The main difference is the nails, and the number of layers is significantly higher.

All the NLT panel layers span in a single direction; this means NLT panels can be used for curves, where the difference between each layer can be offset to fit the curve. Additionally, NLT panels can technically be created on site instead of only at a manufacturing site, so there is some flexibility in usage there.

The International Building Code (IBC) recognizes NLT as code-compliant for buildings with varying heights, areas, and occupancies, allowing for Type III, Type IV, or Type V construction. NLT is created from dimensional lumber stacked on edge: 2″x4″, 2″x6″, 2″x8″, 2″x10″, or 2″x12″ at 1-1/2″ on center and fastened together with nails. Plywood sheathing is often added to one top side to provide a structural diaphragm. Plywood sheathing also allows the product to be used as a wall panel element.

There are different types of NLT and Schiferl said he has seen many types and he think this is part of the challenge for the post-frame industry. “There are no standards. It’s the Wild West when it comes to nail lams. I have seen wire nails with structural finger joints. I have seen truss plates at the joints with 10d nails 12″ o/c. I have seen butt joints with the faces held together with a 2-sided truss plate. I see a lot of nonstructural finger joints used. Not sure what that does, if anything. Looks better than having nothing or a truss plate? And then as far as the lumber used I have seen everything from #2 SPF to high grades of MSR SYP … again, no standards.”

Comparisons

Can glulam and NLT be compared? Schiferl explains that glulam has advantages over NLT in that it is lighter, straighter and easier to notch and cut.

Yes, the two can be compared, said Liz Connor, CE Coordinator and Sales at Unalam, Unadilla, New York, but it has some difficulty. “It’s a bit tricky to really compare the advantages and disadvantages for the two products because their primary uses don’t really overlap. Using glulam as a panel is certainly possible, but is not the most common usage. Whereas, panels are a primary use case for NLT.”

Connor said the main advantage, and a fundamental difference between the two products, is that glulam can be used as any type of framing element: column, beam, brace, arch, truss member, or floor/roof panel. “NLT is intended primarily as a floor/roof panel only, although it could also be used as an axial load only column (like a built up stud),” Connor said. “Glulam provides greater options for curvature and much larger member sizes.”

In terms of NLT advantages, Connor explains that for shrinkage of a wide panel, “Glulam will stay as a solid unit, so all shrinkage will appear between panels (potentially becoming a large gap, or limiting how wide glulam panels can be) … for NLT, each individual board can shrink — creating small gaps between each board, rather than large gaps between panels. NLT can also be assembled with board edges staggered or different sizes, leaving a ‘ribbed’ bottom surface to the panel, which isn’t really feasible with a glulam panel.”

Momb explains that true glulam columns will be stronger, straighter, less prone to warp and twist than nail-lams, and that most true glulam column manufacturers are using much higher strength lumber than what can be obtained from their local lumber dealer. Also, he advises that since nail-laminated columns perform poorly in weak axis bending, they should only be incorporated in fully sided walls, unless appropriately braced.

Also, he said, “In actual testing, 3-ply 2″x6″ glulams fabricated from 1650 msr SYP (Southern Yellow Pine) uppers and #1 SYP lowers have a claimed Fb (fiberstress in bending) of 1900, yet actual testing showed an Fb of 2361. Nail-lam columns with identical uppers and M-29 lowers have a claimed Fb of 1782, yet tested at only 1569. This testing was done by Timber Technologies.” FBN