Proper hoisting equipment and technique make a big difference

By Sean Shields, Structural Building Components Association

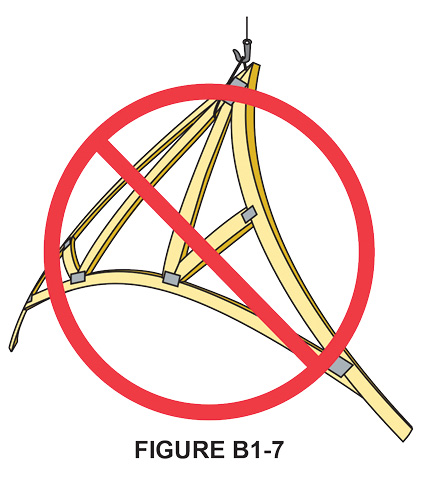

Metal-plate connected wood trusses are used in most post-frame buildings because they are incredibly effective at spanning long distances while efficiently resisting intended design loads (gravity, snow, wind, etc.). As the first two articles in this series outlined, proper handling of trusses is important because significant damage may occur to wood members, plates and joints when a truss bends out of plane that can affect long-term performance (see Figure B1-7).

Lifting long-span trusses with a crane or telehandler during installation is the biggest material handling challenge on the jobsite. This article will explore field-tested best practices with regard to choosing and using hoisting equipment and employing the best lifting techniques. It should be noted that while some of this guidance may seem at first-glance to be “excessive,” just keep visualizing the cost to your business and reputation if an overloaded crane tips over onto the building you are building, or trusses twist out of plane while suspended 40 feet in the air over that building. This article exists because incidents like these are more common than they should be.

Pre-Lift Considerations

The Building Component Safety Information Handbook’s (BCSI) B1 chapter contains a wealth of guidance to installers on best practices pertaining to truss hoisting. The best single piece of advice is located on page 2 of BCSI B1: “Prior to Truss installation, it is strongly recommended that the Contractor involved with the installation of the Trusses meet with the installation crew and crane operator for a safety and planning meeting.”

Length, material composition, and configuration can all have a significant impact on an individual truss’ weight distribution and deformation characteristics when it is suspended or moving through the air. Site conditions and limitations can also affect the truss hoisting process. The component manufacturer (CM) who supplies the trusses can provide recommended pick points and guidance on truss weight. It’s vital this information is given to the crane or telehandler operator in advance of a lift to ensure they use only machinery and rigging equipment with the appropriate size and weight capacity.

These pre-lift meetings should also include discussions of any site conditions that might limit a crane’s range of motion (i.e. utility lines or nearby buildings) or a tele-handler’s path from truss storage to point of installation. Further, the crane operator should provide clear expectations for site preparation or staging that might be required in advance. A common issue is ensuring firm, and relatively level terrain at the crane set up location so the deployment of outriggers can be done safely and efficiently.

Finally, OSHA has established clear expectations in 29 CFR 1926 when it comes to hand signals and line of sight between the crane operator, the pick point, and the set point. A pre-lift discussion should cover these items and ensure compliance both from a safety and risk management standpoint.

Hoisting Best Practices

Trusses may be lifted individually, or in banded groups. Metal or nylon banding is used to help stabilize groups of trusses during transport and handling, but BCSI B1 makes it clear that trusses should never be lifted by the banding, nor should the banding be solely relied upon to securely transfer bundles on the jobsite. When hoisting trusses, materials such as slings, chains, cables and nylon straps should always be of sufficient strength to carry their weight and should be free from defects or damage that impacts their rated capacity. All rigging equipment gets worn over time, and used rigging equipment shouldn’t be taken out of service unnecessarily. However, cuts, excessive fraying, gouges, and kinks should always be inspected and it just makes sense to err on the side of caution when you consider the consequences if a piece of rigging breaks during a lift involving truss or truss bundles weighing hundreds to thousands of pounds. Slings, taglines and spreader bars should also be used in such a way as they don’t cause damage to truss members or joints.

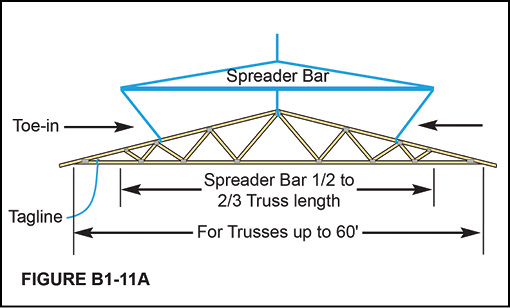

Two of the most common challenges when it comes to hoisting long span trusses is utilizing a spreader bar of sufficient length and using a sufficient number of pick points to avoid damage to wood members and joints. Again, BCSI B1 provides clear recommendations with regard to both these items.

Single Trusses

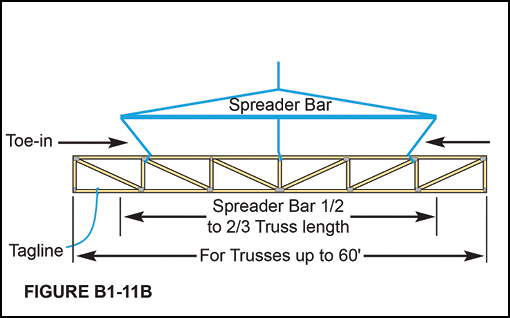

When lifting single trusses over 30 feet, and up to 60 feet, a spreader bar should be used with lines that toe-in to pick points. BCSI recommends spreader bars should be between one-half to two-thirds the overall length of the truss being lifted. Figures B1-11A and B1-11B provide good illustrations of what this best practice looks like.

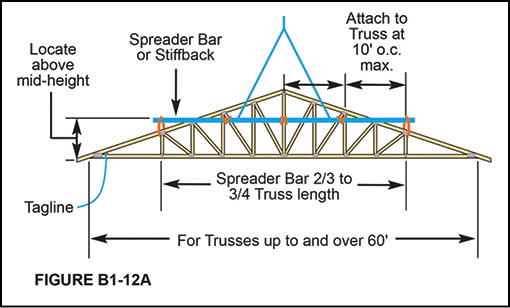

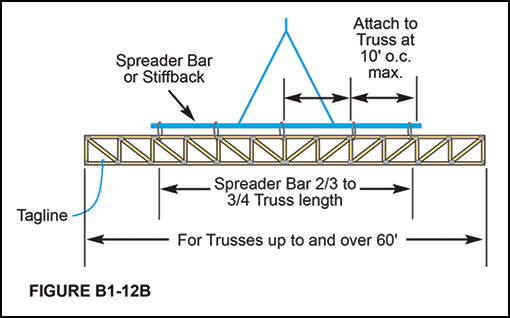

For trusses over 60 feet, spreader bars should be two-thirds to three-fourths the length of the truss and connections between the bar and the top chords and/or webs of the truss should be made at 10-foot intervals. Figures B1-12A and B1-12B illustrate this approach.

These frequent connections may appear, at first glance, to be either impractical or excessive. Yes, while these recommendations are conservative, they are based on countless observations in the field over time. Particularly in the case of long-span trusses, the spreader bar is an essential tool in preventing the truss from lateral bending out of plane. The longer the truss, the greater the forces pulling the truss out of plane and the more resistance that is needed to keep your truss looking like a triangle or rectangle and not a bowl of spaghetti.

Banded Trusses

Another way to resist lateral bending out of plane is to lift trusses in banded bundles. Bundles present a different set of challenges. First, the weight of a truss bundle becomes very important to know to ensure a crane or telehandler’s capacity isn’t exceeded when the boom is extended to its farthest pick or set point. Again, the CM is a good source to supply the weight of individual trusses that can then be combined to determine the total weight of the bundle.

Second, all banding should be inspected prior to hoisting to make sure it is intact and secure. Again, never use the banding to lift the bundles. For trusses between 45-60 feet in length, at least two pick points should be used to lift a bundle (see Photo B1-12). For trusses over 60 feet in length, a minimum of three pick points should be used.

Finally, because of the concentrated weight of truss bundles, special care should be taken to ensure the truss bundles are positioned to not overload the supporting structure. BCSI recommends all walls be adequately braced prior to supporting the weight of the bundle. To that end, consider whether you might need to install additional wall supports or T-reinforcements in the vicinity of each bundle.

The Bottom Line

If something goes sideways during a long-span truss lift, it will go quickly and with very little warning. The consequences can also be devastating, from significant truss damage to building collapse and injuries. BCSI B1 provides field-tested best practices to avoid these outcomes and ensure every long-span truss installation is truly uplifting. In the next article, we’ll look at the best practices within BCSI B2 as it pertains to the installation of long-span trusses. FBN