Galvanizing methods, shank types, testing, and more

Information Provided by Maze Nails

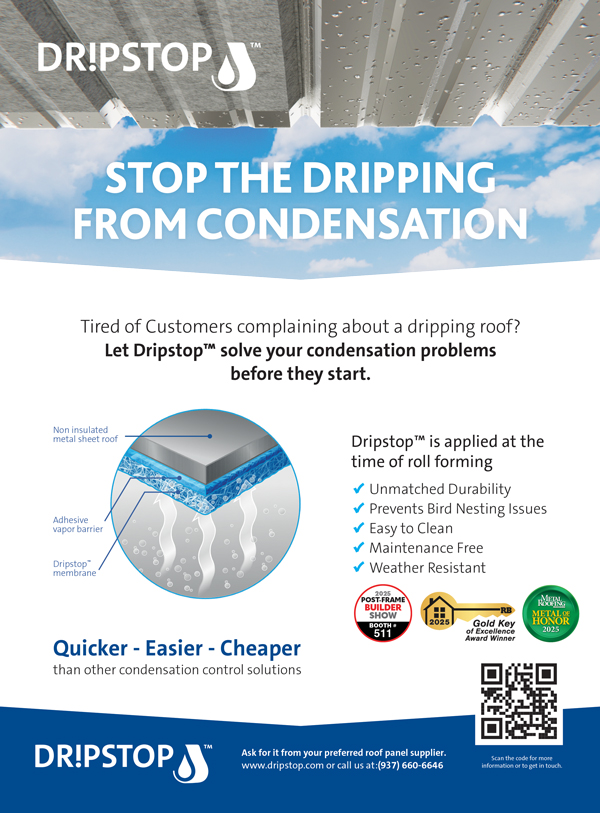

Fasteners: They might be the smallest part of a post-frame build, but they are arguably one of the most important aspects. They are the “glue” that holds everything together and without them, the structure would come tumbling down. Most of the wood portions of a post-frame building are fastened with nails—choosing the right nail for the job may seem like an easy thing to do but, as shown on the facing page, there are many options that can be taken into consideration. Here we will discuss the main varieties used for post-frame.

PHOTO COURTESY OF MAZE NAILS

Plating/Galvanizing Methods

What are the different types of galvanized nails on the market, and what will assure a rust-free build for years to come? To start, galvanizing is the process of applying a zinc coating to a base of steel, with the end goal of preventing rust. Rust occurs when the iron molecules in the steel come into contact with oxygen or moisture, which naturally are found in and around every single building.

It’s how the zinc is applied to the nails that’s so exceedingly important. The performance of different kinds of zinc-coated nails varies tremendously—just ask any contractor or dealer who has been called out on nail-staining complaints.

For dependable corrosion-resistance, steel base nails rely on two critical zinc factors: thickness and uniformity. There are four major processes for applying zinc to steel nails:

1. Hot-dipping: In this process, the nails are completely immersed into a vat of molten zinc, similar to french frying potatoes. This not only gives an outer coating of pure zinc, but also provides a tenacious inner coating of zinc-steel alloy. Some varieties of nails are double hot-dipped for a second protective coating of zinc to preclude pinholes or imperfections, and to increase the amount of zinc on every nail.

2. Tumbler or hot-galvanizing: Also known as barrel-processing, these nails are the type most often produced by big steel mills. Hot-galvanized nails are coated by sprinkling zinc chips on cold steel nails in a barrel, then rotating the hot barrel in a furnace to melt and distribute the zinc. The melting zinc “washes” onto the nails—somewhat like buttering popcorn—and in the same way, the coating can be inconsistent. One issue with this method is that the threads of ring and screw shank nails can fill up with zinc during the process, causing them to not function as intended when driven.

3. Mechanical-galvanizing or peen-plating: This method is a relatively new development involving rolling cold nails around in a barrel with zinc dust, tiny glass “BBs,” and an activator fluid. The barrel rotates and the BBs hammer or peen the zinc dust onto the nails. This results in relatively clean threads but normally only a thin deposit of zinc, which is further buttressed by immersion in a chromate rinse.

4. Electro-galvanizing or electroplating: This method uses electricity and zinc anodes to put on a beautiful, shiny coating—which is also very thin. Electroplating of nails is performed by placing them in a basket, then into an electrolytic solution so that a thin film of zinc is deposited by an electrical current from zinc anodes onto the surface of the nails. Although electroplated nails are beautiful and shiny, it is not feasible economically to build up a heavy enough coating to make this type of nail dependably corrosion-resistant for outdoor use. The thin zinc coating soon oxidizes away, causing electroplated nails to rust quickly upon exposure to the weather…just ask any experienced siding applicator. In short, plated nails have good holding power from clean threads, but they do not have the heavy zinc coating needed to avoid rusting and staining.

Whatever type of nail is used in your specific application, it doesn’t pay to skimp on the nails—cheap nails that rust can be a real heartache down the line for both builder and homeowner.

PHOTO COURTESY OF MAZE NAILS

What About Stainless Steel?

While many associations specify galvanized nails, there are certain applications where stainless steel nails are preferable:

• Marine environments (within 5 miles of the seacoast)

• Cedar and redwood products (siding and decking), where the wood is left natural or treated with a clear wood finish.

• Severe or corrosive conditions, such as fertilizer storage buildings, salt storage buildings, hog confinement buildings, etc.

Shank Differences

When should you use a nail with a ring or screw shank? Smooth shank nails are easy to drive—but they don’t offer much holding power. For that reason, Maze Nail engineers set out to design nails that would hold tighter in all sorts of construction applications. Their mill designed and produced the first spiral shank nails—also called screw thread or “drive” nails.

These nails have a spiral thread, which causes them to turn when they are driven—much like wood screws—and they actually form their own thread in the wood fibers. They offer good holding power and are specifically designed for use with hardwoods and dense materials. Flooring, siding, decking, pallets, and truss rafters are typical applications for spiral shank nails.

A division of Maze Nails also developed an annular (or ring) thread on their nails that provided even better holding power in many applications. Referred to as ring shank, the threads on these nails separate the wood fibers—which then lock back into the rings—thus resisting removal. Ring shank nails are widely used in plywood, underlayment, decking, siding, and roofing applications.

A third type of threading, typically found on masonry nails, is a fluted shank. This thread style gives those specialty nails excellent holding power in concrete block and masonry applications. The horizontal threads “cut” the masonry to minimize cracking.

Warning:

Milled face hammers are not recommended for driving galvanized nails. The highly abrasive surface of the hammer-face may compromise the integrity of the zinc-coating on the nail head, reducing its corrosion-resistance. Smooth face hammers are recommended.

Field Versus Lab Testing

When choosing the right nail for each job, how much faith can be put into testing? Lab tests are great…for some things. But not when it comes to evaluating the rust-resistance of one type of nail compared to another type. Some lab tests, especially “salt spray,” can’t accurately simulate true weathering conditions for nail applications of roofing, siding, and trim.

For example, under the abnormal lab conditions encountered in the salt spray test, the typical “reaction product barrier” that protects hot-dipped nails is not allowed to form as it would in the “real world.” It is this oxidation barrier that allows hot-dipped products to resist nature’s attacks—and ensures long-term corrosion protection. Salt spray testing doesn’t allow this important layer to form—resulting in misleading results.

Before you choose nails based on lab tests, ask for more information about the true tests—actual field experience and number of callbacks. FN