By Jacob Prater

Dimensional Lumber Types and Some of Their Properties: Selecting between and within wood types.

The 2×4: It’s everywhere and we use it all the time; however, not all are created equal. Of course, you need to meet the specifications for any building project, but sometimes you do have choices and they may vary by species or wood type, where and how they are produced, and how they are treated and stored before they get to you.

So, why might you want one type of wood over another? And how are they different? Is tighter grain better than wider grain? These are questions that can be answered generally while noting that there may always be an exception to general rules.

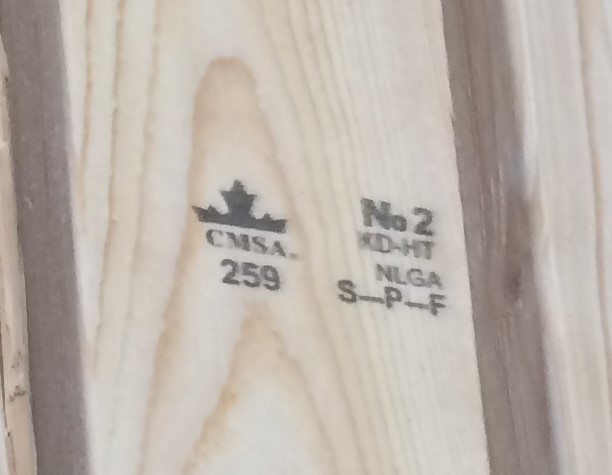

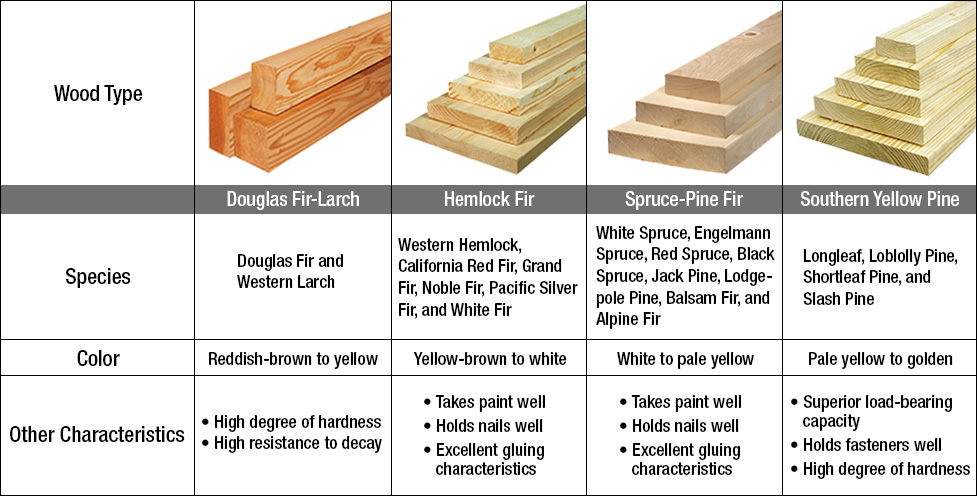

Most construction lumber falls into the category of softwood, which means that it comes from gymnosperms (means naked seed), which are chiefly conifers such as hemlock, spruce, fir, and various pines. While softwoods vary in their strength properties and density, they are typically grouped and sold under a comparable stamped product that meets similar engineering properties. These groupings really simplify choices and help to keep quality and strength controlled on the purchasing end as sawmills may be getting different species coming to them due to changes in the logging industry and what is being cut.

Examples of these groupings are SYP, Southern Yellow Pine; DF-L (or Doug Fir-L), Douglas Fir and Western Larch; Hem-Fir, a combination of Western Hemlock and various true Fir species; and SPF, a combination of Spruce, Pine, and Fir (listed in order of strongest to weakest). These groupings will be stamped on the wood you purchase like the example of S-P-F in Figure 1. Different species certainly have advantages over each other in different categories including everything from looks to resistance to warping and, of course, strength.

Figure 1. S-P-F stamp for Spruce, Pine, and Fir. photo by Jacob Prater

Strength is a critical factor in many uses; to be sure the right material is used, all you have to do is use the correct grade and type of lumber prescribed. But you can also make choices within available wood and get a stronger product or you can use the stronger product (wood type) within that grade if it is available, if it suits your needs, and if the price is right (sometimes they don’t even get priced higher).

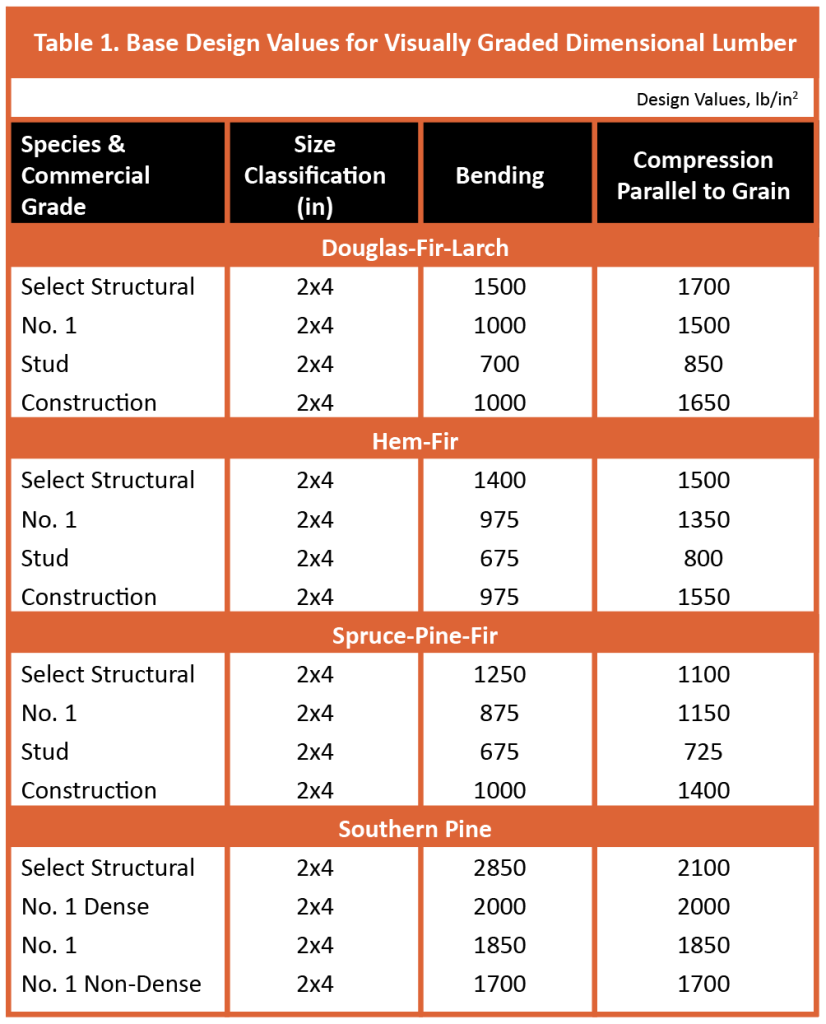

Among the strongest softwoods used in construction is Southern Yellow Pine with Douglas Fir a close second, while White Pine is on the lower end with Spruce and Hemlock rounding things out in the middle. A basic understanding of strength for lumber types is displayed in Table 1, where the design values for the previously mentioned lumber groupings can be compared for bending and compression strength. Bending strength affects how the wood responds to spanning while compression strength here is related to the load bearing of a stud.

Strength isn’t the only thing that might matter though. Sometimes strength-to-weight ratio may be important, in which case Spruce is the best option. While species choice can be important, Shuva Gautam (Forestry Professor and Teacher of Wood Products) stresses that it is often more important how a product is treated and stored before and after you receive it. In essence, the drying process and then the conditions of storage will dramatically affect straightness of the lumber within a particular grade and wood type.

For constructing climate-controlled buildings, kiln dried wood that is then stored in climate-controlled conditions would be ideal. While for non-air-conditioned buildings kiln dried wood that is then stored under cover might be better. The issue in each instance being acclimating the wood to the moisture conditions where it will be after construction so that it remains as dimensionally stable as possible.

In addition to the dimensional stability of wood and the moisture environment, the physical act of drying it, particularly kiln drying it makes the wood stronger. Kiln drying is standard for construction lumber to ensure a quality product, but you will want to make sure that wood stays dry afterwards.

Factors Affecting Strength

Given that some species are generally stronger than others, there is also variation within a species in terms of strength of the wood product you may buy. Several factors may affect the strength of wood within a species including tree age and growth ring thickness. Softwoods grow two different types of woody material: earlywood and latewood. Latewood is stronger than the earlywood and, as a result, when there is more latewood in a particular piece of wood it will be stronger. This latewood is the darker-colored material in softwoods and is grown on the tree in the latter part of the growing season. Latewood is more dense owing to thickened cell walls and has greater strength properties than the lighter-colored earlywood. Most of the time more growth rings per inch of thickness means there will be more latewood in the board. This, of course, translates to older, bigger trees producing stronger wood.

Tree growth rate affects wood strength in addition to the variation in species. And this one is a little tricky. As a general rule, softwoods will be stronger if they are growing more slowly (hardwoods exhibit the opposite with faster growing trees yielding stronger wood products). There is an important distinction that should be made about growth rate here: The real point of this is about tree age. While growth rate does affect the density and strength of wood in some species, the more important factor is that as softwood trees age, many of them will form denser and thus stronger wood than when they were younger and growing more rapidly. The major distinction here isn’t really growth rate, but ring thickness and how the tree is laying up wood. In other words, if you have two old trees (same age) of the same species and one is growing faster than another, there isn’t necessarily going to be a lot of difference in wood density and thus strength. But there will be a difference in the wood between a 20-year-old tree and a 120-year-old tree. As a bonus, that wood from an older tree is also less likely to have knots in it.

Juvenile Wood

With this knowledge, you can make choices at the lumber pile based on the thickness of growth rings, but remember: If it makes the grade that you need, it makes the grade that you need. Things that you might avoid if you can would be wide growth rings and lumber that includes the center of the tree. Avoiding these could help you avoid what is called “juvenile wood.” Juvenile wood is the rapidly growing wood of any tree. This wood will be formed at the top of the tree but remains in the center as more wood is laid on around it each year as the tree grows vertically. This juvenile wood is flexible and serves the tree well in bending in the wind, but as a result it is not as strong as wood that is put on later.

The difference in this juvenile wood has to do with the orientation of the layers of the cell walls within the wood. In juvenile wood the layers of cell wall are all oriented in roughly the same direction, whereas in wood laid on later the layers in the cell walls are at an angle to each other, making the wood stronger (think about plywood and how the layers are crossways to each other).

Strength and Location

Growth rate, ring thickness, and thus strength and wood density are also affected by where the wood is produced. The more northern parts of the range where a species may be grown will cause trees to grow more slowly laying on thinner growth rings and denser wood. As a result of this, some Spruce that is grown in Canada may be exceptionally hard, dense, and strong while in contrast fast-grown Yellow Pine from farther south may be softer and weaker than expected (evidence of this is in Table 1 where you can see there are three types of No. 1 Southern Pine relative to density from growth rate).

To be fair to the species that make up Yellow Pine, when it is grown slowly (massive old trees) can be incredibly hard and dense as evidenced by the use of reclaimed “Heart Pine” used as flooring. Even though some of this more rapidly grown wood (you’ll be able to see the ring thickness) may be weaker, it still makes the grade that it is stamped with so you should not be afraid to use it within that grade and for its application. The plus side to rapidly growing trees and shorter rotations on timber plantations (sometimes as little as 25 years between planting and harvesting) is that wood can be produced faster and more economically than slower-growing wood, thus giving you a good and very useful product at a lower price. The savvy builder will use the best wood available for each application, the strongest as required, the straightest where it’s needed, the pretty where it’s exposed, and the knotty and rough where it is hidden and doesn’t require strength.

If straightness and resistance to warping are important to you then the grain orientation of the wood may be more important than species, though some species are more known for warping. The ideal grain orientation for the dimensional stability of lumber is to have the growth rings crossing the wood in the shortest direction and the grain running parallel to the length of the board (called quartersawn). The closer any piece of wood is to this ideal grain orientation the more dimensionally stable the board will be (see Figure 2).

Wood Selection

Between species, ring thickness, grain direction, and how the wood was stored one can be easily overwhelmed with choices, so what is the best course of action? For good or ill there are not always choices and at times you have to use what is prescribed or simply what is available. A quick look at a qualitative comparison chart (Figure 3) might tell you all you really need to know aside from strength.

Dan Heinen, contractor in eastern Kansas for over 50 years, says, “On commercial jobs everything is usually dictated even down to wood species, but you have some choices in other construction.” Dan also commented that when you order a bunk of wood you “get what you get,” which may mean varying quality and a wood species that you may be less familiar with (Figure 4). He stressed that if you have the time and can pick through a pile, it can make a difference in how quick and easy your project is to build, but that “you have to have the time to pick through a lumber pile.”

In light of the fact that different species have their own characteristics related to how easy they are to work with, woods such as hemlock, while strong, may not be a great choice in some circumstances due to their likelihood to warp and twist (you might avoid putting sheetrock on them). Other woods such as Douglas Fir might be straighter and strong but vary in quality quite a bit. What you choose to use is application-dependent and availability-driven, but when pressed if he had a choice of wood species Dan Heinen responded, “I love working with White Pine. It’s lighter and softer, but it doesn’t split out as much when you nail it up, and it looks better where exposed.” Certainly, taking fasteners without splitting and holding them well is something to be considered and in this category as the wood gets denser it is more likely to split when nailed.

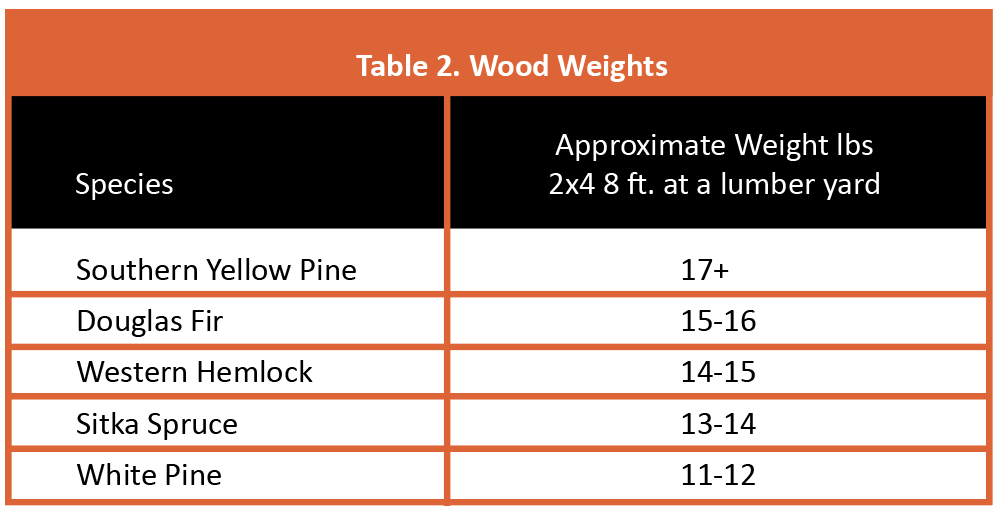

Another part of Dan’s preference mentioned the weight of the wood. How much each individual piece weighs can certainly add up and be important when it comes to handling the product at all stages. A 2×4 8-foot can vary from about 17 lbs. for Southern Yellow Pine to 11 lbs. for White Pine (Table 2). That means that three Southern Yellow Pine 2x4s are close to the same weight as five White Pine 2x4s. That’s enough to make a clear choice if you are handling it by hand all day and you don’t need the added strength of the Yellow Pine.

When asked if lumber today was better or worse than decades ago, Dan responded, “There has always been junk lumber and good lumber.” He then stressed that having a good supplier always helped to ensure good product, but that in any ordered bunk of lumber there are some lower quality pieces and you just use those where it matters less, but all of it makes the grade as stamped. FBN

Jacob Prater is a Soil Scientist and Associate Professor in Wisconsin. His passion is natural resource management along with the wise and effective use of those resources to improve human life.