Building Beautifully is a Contractor’s Most Effective Weapon

Many builders working in towns and cities have experienced public opposition to their projects. Whether they’re using pre-engineered metal systems, masonry block, tilt-up, or stick-frame, anyone from zoning officials to next-door neighbors can complain about the location, the height, the exterior finish, and the architectural features of a project.

Post-frame builders, on the other hand, sometimes face a more serious problem: objections to the whole idea of post-frame. The hostility may be from town planners who think of “pole barns” as temporary structures. It could be from zoning officials who distrust the integrity of a building without continuous footings. Or it could be anyone who views post-frame buildings as necessarily unattractive, utilitarian structures.

Occasionally, opposition takes the form of an actual ordinance that effectively prevents or discourages builders from using post-frame construction — generally by prohibiting wood-to-ground contact, requiring full footings, or banning wood trusses or metal siding. Whether it’s spur-of-the-moment hostility or written law, such “zone-outs” are a potential obstacle for any post-frame builder working in populated areas.

Some objections are based on a simple lack of knowledge: that wood treatments give embedded posts lifespans exceeding 50 years; that properly designed post-frame structures can withstand tremendous wind, seismic, and snow loads; that post-frame buildings can be built to meet most fire codes.

In Zanesville, Ohio, building maintenance supervisor John Benson recently objected to post-frame on several grounds. “A pole barn doesn’t have a very long shelf life,” Benson said. “(It) just wasn’t going to be a good investment.” The NFBA promptly sent the town literature on post-frame design’s strengths.

More common are aesthetic concerns. The post-frame method was born on the farm, and is best known for its economies and structural efficiencies. The sameness of many rural post-frame buildings, with unaccented 3:12 roof pitches and the same color and style of metal siding and roofing, reinforces the “plain pole barn” stereotype.

The strong association of post-frame with utility buildings trumps the fact that post-frame can be dressed up as well as any building, and that many retail stores, homes, churches, and even schools have been built with the method. Post-frame builders can use a variety of exterior materials and colors, can change roof pitches, and add architectural features.

Still, the fact is that many don’t — usually because their budgets won’t permit such frills. The best way to avoid a zone-out may be to construct a quality, attractive building, but convincing customers to budget for beauty can be a challenge.

“A pole building doesn’t have to look like a Kleenex box with a roof,” says Pennsylvania builder Mari Plowman.

While there clearly isn’t a vast conspiracy against post-frame, examples of zone-outs crop up throughout the country. Stories have circulated of industrial parks prohibiting wood buildings, of zoning board nepotism or cronyism favoring steel structures, of the need for tax revenues pushing alternate construction methods, of historical preservation committees giving post-frame the thumbs-down. In Missouri, a town legislated against concrete materials commonly used for post-frame footings.

Minnesota builder Rich Rothstein sees zone-out all the time. “A lot of the city planners attend conferences with the same people, and their big deal is they want to eliminate metal-sided buildings,” he says.

Zoning officials aren’t the only ones spreading negative vibes. In some places, competing builders do what they can to question post-frame’s viability. “We have enemies in our own ranks,” says Plowman. “Stick-frame builders who haven’t seen what we’ve built, they call it ‘pole building,’ and think it’s hilarious.”

“Zone-out is not an epidemic, but if you passively sit by and do not address it, it’ll creep up on us,” says Ron Sutton of Morton Buildings. “It’s a very elusive thing to fight.”

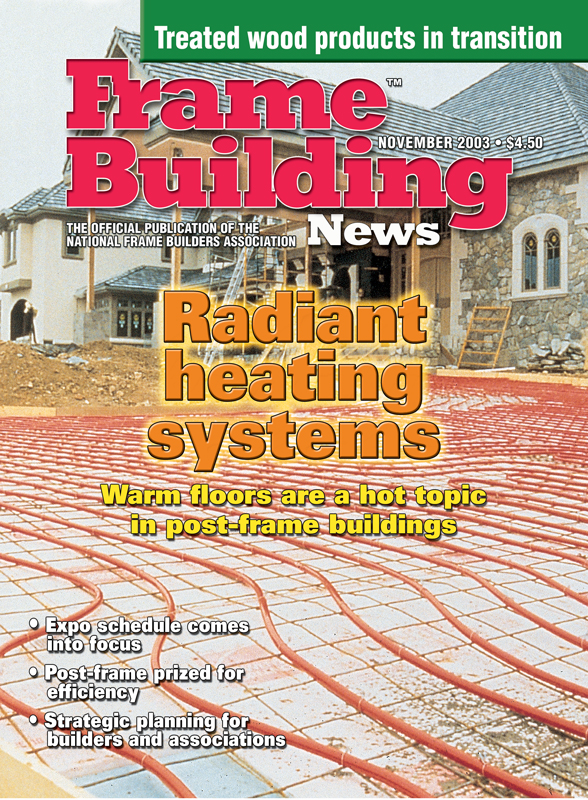

A brick office space with plenty of windows fronts a warehouse. Wick Buildings photos

While both of these post-frame buildings serve their purpose, there’s no question which is more suitable for high-visibility areas. The computer store at top has a brick exterior, steep roof with composite shingles, and attractive entryways. The rural storage facility at bottom features white, ribbed metal roofing and siding. Wick Buildings, Frame Building News photos

Confronting Zone-Out

When, where, and how to confront post-frame zone-out is also elusive. Sometimes, a customer doesn’t want to spend the time and money to fight.

“One of the real challenges is the issue of time,” says Sutton. “A client wants a quick turnaround on their building, they don’t want to go through a zoning appeal, the pain of getting an exception. Secondly, they aren’t married to post-frame construction. They’ll just go with what’s acceptable. From the contractor’s point of view, it’s no good if you’re spending your time fighting just to build.”

Perhaps the more effective tactic is to fight a preemptive battle on behalf of post-frame. Fire, safety, and longevity objections to post-frame can be rationally and effectively countered with NFBA literature and engineers’ testimony, but negative perceptions of post-frame aesthetics are more harmful. Convincing the public that post-frame buildings can, in fact, look good is a top priority.

“I think it’s a misconception, people think we’re building their grandfather’s pole barn,” says Wick Buildings’ Gail Miller. “We’ve come an awful long way from that.”

Since the public generally isn’t aware of post-frame’s design flexibility, builders should have portfolios highlighting their most attractive jobs. The NFBA does what it can, with its Beautiful Buildings Brochure designed to showcase upscale uses of post-frame, but as Plowman points out, the literature is seen by a small percentage of people.

“We’re singing to the choir,” she says. “The Beautiful Buildings Brochure is a step in the right direction. Every township official ought to have a copy along with a personal letter from the post-frame company closest to them. (The builder should) offer to show them some of their buildings, take them to lunch.”

But Plowman concedes such an initiative would be costly and time-consuming. A more attainable approach would be for post-frame contractors to consistently strive to erect the best-looking building possible, within a customer’s budget and appropriate to its location. The process starts with the sale.

“In sales, you never achieve success greater than what you shoot for,” says Sutton. “If you aim to sell a commodity product, that’s what they’ll buy. If you show them what’s available, you’ll be more successful. We’ll turn down some projects, say if the client just wants a machine shed for a church. If they want something that’s not appropriate, then they’re not a client we want.”

But plenty of customers are willing to listen to and consider the advantages of a dressed-up building.

In the same vein, Sutton stresses the importance of designing buildings appropriate for their location. An all-steel-sided structure constructed on Main Street would not only look out of its element, but might dissuade town officials from allowing a similar building style in the area in the future, regardless of any aesthetic improvements.

“The industry has to come to grips with having the character not to put inappropriately designed buildings in spots where they shouldn’t go,” he says. “You put a tin box in a downtown in rural America, the town fathers will say ‘That’s a piece of junk.’ That’s how some of these zoning ordinances happen.

“We need the fortitude not to give in and sell a commodity product where it’s not appropriate.”

Beating Zone-Out

Once a customer is sold on upgrading the look of their post-frame building, there are plenty of options for dressing it up.

Start with siding. All-steel siding is a post-frame standard, and serves as an integral structural component. And there is no denying that steel cladding has produced beautiful exteriors. But that’s often not enough to please zoning boards.

“The majority of our cities around here have stipulations where you have to have at least 50 percent non-metal surfaces; in some of them all your street surfaces have to be non-metal,” says Rothstein.

A masonry look can satisfy those concerns. Using traditional brick as wainscot, or even as the entire exterior wall façade, will pacify some zoning boards, but material costs add up. A lower-cost alternative is Moderra Concrete Siding, a thinner, mortarless brick facsimile that is making its way into widespread use. Novabrik sells a similar product.

Another way to avoid all-steel façades is to design a stucco look, with products like Dryvit and Neogard. Using a wood siding like T-111, cedar clapboard, or spruce board and batten can give a building a rustic look.

As for the roof, the post-frame standard is a ribbed metal panel on a 3:12 or 4:12 pitch — perfectly acceptable structurally, but the low slope has a strong association with utility buildings. Raising the pitch to 6:12, 8:12, or greater helps, as do conventional asphalt shingles or cedar shakes. People like buildings that look like their homes, says Wick’s Miller.

“I think it’s extremely important for acceptance,” he says. “A lot of people want the same pitch on post-frame buildings as they have on their house, and want the same shingles as they have on their house.”

Metal does have a place downtown. Metal roofing manufacturers produce tile and shingle facsimiles virtually indistinguishable from their authentic counterparts. And more and more designers are specifying architectural metal roofs, including standing seam systems, in part because of the improved performance of panel coatings.

“We had a situation where a guy in our office went to a zoning meeting,” says Rothstein. “They had in their zoning no pole barns, no galvanized steel. He went in with our product information, showed them the performance standards of Kynar paint, and it was approved no problem. (Zoning boards) are really, really leery about buildings being cheaply done, with paint fading and peeling in the not-so-distant future.”

Coatings improvements aren’t just limited to fade and peel resistance. Today’s steel coating options include colors spanning the rainbow, and opting to incorporate several on a building can make a statement.

“There are a lot of little touches that really don’t cost anything with post-frame buildings,” says Wisconsin builder Francis Herr. “When people are choosing colors they shouldn’t be constricted by other building colors, they should be more daring.

“At one time it was really popular on the farm for buildings to be all the same color, and it looked nice, it served its purpose. But now we’re seeing a lot more daring with color selections, brighter colors, darker roofs. I like dark roofs, they can really set a building off.”

Adding elements to the roof, like a false dormer, helps, as do well-designed entrances and porches. Incorporating nicer windows — or just incorporating windows, period — is a plus. Historical commissions have required Plowman to specify windows from Pella, Marvin, and Kolbe and Kolbe for past jobs.

Convincing architects to design post-frame buildings would help make these features more commonplace. “Some of them don’t have a clue, the curriculum never includes post-frame construction,” says Plowman, who describes the members of her company as “wannabe architects.” “We have architects on our side, we’ve made them see the light, and a few of those groups refer customers to us.”

Competitive edge

Post-frame buildings have made their mark by being inexpensive and quick to erect, which has been both a blessing and a curse. But convenient, functional buildings do not have to be bland, and post-frame builders who take the time to sell their customers on good-looking buildings will find themselves in an advantageous position.

“It gives us a competitive edge,” says Plowman. “We can offer creative buildings that are still quicker to build.”

Zone-out busters: Concrete siding

Masonry exteriors are widely accepted, but when used in conjunction with post-frame, costs can be prohibitive. Moderra Concrete Siding, which is starting just its second building season of availability, offers a cost-effective solution. Made of high density concrete, the product is integrally colored and has a natural split-face texture. The units are held in place by aluminum channels. “If somebody wanted that split-faced block look, we didn’t have a lot of options,” says Minnesota builder Rich Rothstein. “This gives us another option.” Another key feature: no masonry subs required. “The people we put out there to build the building can also do this, you don’t need to hire anyone else,” says Francis Herr of Dorchester Builders. Novabrik makes a similar product, which needs no brick ledge or steel support. The company says the product is good for remodeling with vinyl or aluminum siding.

Moderra Photos

Zone-out busters: Seamless coating

The folks at Neogard are in the elastomeric seamless coating business, selling waterproofing systems for walls, roofs, and floors, above and below grade. But, working with Energy Panel Structures, Neogard showed how it can be used aesthetically. The product comes in three different textures, can be applied over steel wall panels, and is available in a wide range of colors. EPS photos

Zone-out Busters: Metal roofing

Metal roofing has long been a staple of post-frame buildings, but not like this. The standing seam style, top, continues to gain acceptance among architects for its clean lines. The post-frame horse barn below is sided with half-stucco walls and has a long-panel metal tile roof that goes on directly over purlins. Development Design Group, Met-Tile photos